Oral supremacy in the USA – Part One

One particular story so far basically untold in its wholeness is that which reflects upon what had happened in the quest to eliminate communities that greatly used sign language, can be told here for the first time by way of how different elements are brought together. There’s no doubt few have made any comparisons between the native American Indians and the Deaf, apart from some research on the sign language of both communities. Progress was problematic for both – especially in terms of the various protagonists who by one means or another sought the assimilation of those very communities. ‘Progress’ for the aforementioned communities indeed brought about dire situations whose effects are still being felt to this day.

Indeed in much the same sense as during the 1940s and 1950s where the oralists attempted to introduce or enforce new programmes that would accelerate the Deaf from a signing community into one that spoke comprehensively, which again was a pretext for eliminating the Deaf and perpetuating the banishment of sign language, can be seen similar attempts towards the Indians in the same period. For example between the 1940s and 1950s a programme was devised to remove the ‘Indian Problem’ for once and all.1 This involved a programme to close down all remaining reservations and assimilate the natives into the cities. It was yet another attempt by the status quo to impose a distorted doctrine upon a minority group. Essentially no matter what – whether its the Indians, Aborigines, Africans or even the Deaf community, and wherever it was, new ideas were always being promoted to tout one form of assimilation or another.

The Oral Supremacy in the USA articles is a work that combines various narratives which utilises the experiences directed upon plus the modus in the aspirations of the white colonial settler (this had originated from a Christian religious notion that both the Deaf and the American natives were not people of God and that it was important to reset their lives (eg implement religious conversion) so that they became Christians and led what were thought to be fulfilling and satisfying lives, including, belief, prayer, expressed morals and perhaps above all, held a high regard and deep love for the Kingdom of Heaven and its omnipotent overseer) plus Native American Indigenous studies and Deaf studies (the debate between manualism/sign language and oralism/audism), as well as the expositions from those such as Alexander Graham Bell, Samuel Gridley Howe, Richard Pratt, George Armstrong Custer and others in order to illustrate a coalescent movement that had both the Native American Indigenous people and the Deaf peoples focussed as being the target for an expressive assimilation to be desired and implemented by that very movement.

Perhaps more importantly is how the doctrines of both racism and oralism were unwitting collaborators – and its something that has very substantially not been recognised, even among academics. Hence in large its why the title of this piece ought to be ‘De-signing America’ – because there was a notion the status quo could clear the continent of its sign language users. Any designs for any form of ‘de-signing’ are inevitably oralist and audist. Certainly ‘de-signing’ occurred everywhere – and elements of that doctrine can still be found being applied in many places under a number of masks the status quo utilises – and its what Harlan Lane describes as a masked benevolence – being ‘an indictment of the ways in which experts in the scientific, medical, and educational establishment purport to serve the deaf, describes how they, in fact, do them great harm.’2

In the States a two pronged approach was made. One was of course the classic battle between the oralists and the deaf, and how Gallaudet worked with Le Clerc and others to ensure sign language did not fade into history, and also to resist any incursion by many avenues including those under the slipstreams created by Alexander Graham Bell. The other being the battle between the settlers and the Indians is evidently far less known. Yet again the slipstreams were quite similar even though that against the American Indians had perceivably begun much earlier and in much stronger form. In terms of both avenues there was a commonality which is that sign language, being no matter what community was using it – the Deaf or the Native American Indians – was comprehensively banned.

Like the Deaf themselves, the natives could continue to use sign language within their own communities. However in terms of the education institutions and boarding schools set up for both, sign language was banned. The dominant tongue – that of the comprehensive and overbearing oral system – was to be the medium by which the disaffected parties would get to know their new futures. These would be without sign language. For the Deaf it was a one step removal from signing to oral method. For the Native Americans it was a double step removal – this being both their native tongue AND their native sign language were pushed aside in order that they could learn the white man’s English.

The fact the Natives’ plight had come about is because of racism. There is no doubt about that. Their sign language was seen as part of a culture that had no place in the modern world. It does not matter where it occurred, colonialism was also about removing every semblance of culture and identity the natives had held very proudly – and then forcing them to fit in with a dominant paradigm. This too can be seen in how the oralists – or hearing people – viewed the Deaf. The colonialisation of the Deaf was based upon the removal of their sign language and the imposition of an oral medium. That too removed the unique culture and identity the Deaf had, hence it was quite evidently of a racist endeavour too.

‘History without Silos’ is seen as a specialist an approach to scholarship and organisation which emphasizes an interdisciplinary interweaving of different sources – and this breaks down the rigid boundaries that can limit historical perspectives and knowledge. Silo-ization is a form of tunnel vision which limits the fall out of potential histories. Instead of being conservative with their historical output, historians are required to employ diverse sources in order to create a more complete and nuanced understanding of the past. It encourages building bridges between different academic fields, or even different departments within a company, to foster creativity and innovation. Hence Oral Supremacy in the USA is an attempt at avoiding silo-ization. It brings diverse sources together and as a result it gives a more complete understanding of the past. In return it reveals some shocking aspects never previously discussed, at least not in substantial ways, and which had arisen from unexpected ways.

It relies upon many texts not illustrated previously including much recent work that has focussed in those areas where substantial gaps are missing. These include the assimilation of the Deaf and the American Natives and how these endeavours basically ran in parallel, as well as filling gaps in the Martha’s Vineyard history and examining means and ways that Alexander Graham Bell had investigated or promoted. All this along with other well noted historical accounts (such as those of the US Military leaders General Pratt and General Custer) come together to demonstrate a comprehensive history that had at its heart the imposition of the white man’s ideal and the elimination of what were seen as outdated or recessive cultures. There’s no doubt the waterfall of thought and opinion that arose too aided the notions behind the comprehensiveness of colonialisation – because again it was the white man, the white European ideal, that was at the very core. And since America, indeed the United States was, to all purposes and intents, a colonial empire, there’s little surprise the deleterious effects of the white settlers caused so much pain, not just among the Indigenous American Natives, but also the Deaf people in that country too. The main thrust of the work is to show how the spoken (aural/oral) white ideal had caused such a whirlwind of change.

The text in this article could be considered as a series of notes intended for further discussion. It is not meant to be an authoritative work on the subject because there still are gaps in the various threads that have been discussed and also the different sources that have been used. Nevertheless, the elements of oralism, racism, colonialisation and assimilation no doubt have a commonality across the spectrum of ideas and intents that were employed and enforced. This work by Deaf21 presents a fresh and critical look at those histories.

1) Prologue – The Long and Winding road to Little Big Man and Greasy Grass

In the beginning the earliest use of sign language recorded is that by Cabeça de Vaca in 1528, when he observed Timucua Indians in Tampa Bay (now part of Florida) active in that method. During de Vaca’s travels he noted many tribes used different languages ‘however he questioned and received the answers of the Indians by signs “just as if they spoke our language and we theirs.”‘3

That record is from Garrick Mallery’s Sign Language among North American Indians (1881).4 In addition to that, Mallery also adds that ‘reference may be made to the statement in Major Long’s expedition of 1819, concerning the Arapahos, Kaiowas, Ietans, and Cheyennes, to the effect that, being ignorant of each other’s languages, many of them when they met would communicate by means of signs, and would thus maintain a conversation without the least difficulty or interruption.’5

Hence we know the North American Indians had their various tribal dialects, but a common sign language was practised right across the different tribes. Evidently it did not matter whether they could understand each other orally, because they had sign language and it was no doubt a very important method of communication.

This excellent system of signing served exceedingly well until the whites had arrived from Europe. In the early years there were few, if any, problems. However when the Pilgrim Fathers set out from Plymouth during 1620 aboard the Mayflower across the Atlantic to the ‘New World,’ that very historic moment, as important as it was, there is every indication the Pilgrim Fathers had a considerable amount of intolerance – and this set the scene for what would become eventual conflict with the Native American Indians. As a result of that by the early 19th Century assimilation would be very much on the cards.

‘These were people who came here for their religious freedom because they couldn’t worship as they pleased in their own country, and yet when they came to this country they did not seem to have that same tolerance for the people that they met here, despite all that the Wampanoag did to help them,’ said Paula Peters, a member of the Mashpee Wampanoag Tribal Nation… ‘You can’t have a colony without someone being colonised.’6

It was also part of the long road towards an eventual mortarium that saw sign languages banned among the natives but also right across the world in terms of the sign languages used by the Deaf. And that because these different groups,. by way of having a different form of communication, could not be seen as having any sort of affinity with the religious beliefs of the times. They were seen as beings that were unable to communicate with God hence this ‘wrong-doing’ had to be corrected. Thus began the endeavour to assimilate, to convert these groups into an ideal that matched the needs of the white, Christian, colonialist, missionary invaders.

In the days following American independence in 1776, the days drew ever closer when the natives would have to face restrictions and limitations under newly passed laws by the US Government in the early 19th century.7 Little of that worked and eventually the might of the US Cavalries were set upon the natives. The Calvaries’ basic task, it seems, was to round up the Natives into reservations, and failing that, to decimate these precious indigenous communities along with their centuries old traditions, culture – and also their proud sign language.

Within those far off days, it was made out that a certain Jack Crabb had lived through some of the most momentous events of those times – including the Battle of Little Bighorn. As good a story it is, that of Jack Crabb was a mere fiction. Instead it was the result of intensive research within material that had been little referred to, but it certainly carried a lot of connotation on what really had happened. Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man – a work applauded because of its accuracy detailing just exactly how those old days had been. There simply was no romance to the Old Wild West as many had tried to make out – this being largely one of heroics and morality. Instead Little Big Man was a revisionist historical book which set out to prompt the truth about what had happened. The book, as Berger put it, was something he began ‘in 1962, with the idea of bringing together all the great themes of the Old West that we, in the 20th century, looked back on as legendary.’

Berger made use of a large volume of overlooked first-person primary materials, such as diaries, letters, and memoirs, to fashion a wide-ranging and entertaining tale that comments on alienation, identity, and perceptions of reality8.

The surprise is this largely unseen material was not hidden anywhere. Berger did not travel anywhere specially to research his work but merely used libraries and archive centres to source material for his book. Thus he essentially avoided falling into the history silo trap in terms of his novel because it employed so many historical perspectives and views, and it in turn garners a far richer and more comprehensive overview of the plight that was faced by the Sioux and Cheyenne and the white settler’s endeavours to subvert and even to eliminate them.

Certainly there is a lot of stuff out there that remains substantially unresearched. In a sense what Berger did is important because without these tools the truth may have never been known and the world would have endured the glory of General Custer for all eternity. Of course that is pushing the envelope a bit, but on the other hand that is what this Deaf21 article sets out to do. Almost the entire work here has not been published before in this particular context – and its of course a source material of various considerations indicating there was nothing glorious about any of the events that had took place.

Part of the 1965 front cover of Thomas Berger’s Little Big Man. The book was originally published in 1964.

In both the book and in the 1970 film Jack Crabb is a picaresque yet fictional protagonist who gets to witness the events at Little Bighorn – or Greasy Grass as the natives knew it. In those days Montana was still a wild part of the American West. Railroads had not made their way yet. The Utah and Northern Railway was the first to reach the area in 1880, followed by the Northern Pacific with a route over the Homestake Pass across the Continental Divide towards ‘The Richest Hill on Earth.’9 That railroad is now closed and people these days explore the Homestake’s abandoned rusty rails10 as if it is some sort of Wild West!

In those far off days even Yellowstone (which borders Idaho, Montana and Wyoming) had barely begun life as the world’s first ever National Park. Little Bighorn is some distance to the east of the park and it marked one of the most tumultuous events in American history. It was where one of the greatest heroes of the United States – General George Custer, had fell in battle. When its said he was a hero, that is what all the books said back then. Today we know very differently.

Despite being white, Jack Crabb had been brought up by the Cheyenne, thus he had experienced their trials and tribulations at first hand. As for ‘hand,’ what that evidently means is Crabb knew their sign language and how important it was for their communication to be made with signs.

But before the sun had got far through the sky, I had learned quite a vocabulary of the sign lingo and conversed with Little House on such things as could be expressed with the hands. For example, you want to say ‘man,’ so you put up the index finger, with the palm facing inside. Of course I was considerable assisted in learning the lingo by Little Horses’s habit of making the sign, then pointing to the thing itself. The motion for ‘white man,’ a finger wiped across the forehead to suggest the brim of a hat, was something difficult to savvy owing to Little Horse himself wearing the felt hat I had discarded. He kept running his finger along the brim and pointing at me, and I first thought he meant ‘you hat,’ or ‘you,’ before I got it straight. The sign for plain ‘man’ naturally meant ‘Indian Man.’ (Berger, Little Big Man, P48)

Just as Crabb knew how the Cheyenne had lived, he too knew just how the settlers hated the Indians. He had determined the white man’s protagonist, a certain George Armstrong Custer, should be eliminated. Crabb desperately wanted to kill Custer. It was a desired revenge for what Custer was doing to the Cheyenne. Crabb was always moving north, in the hope he would find Custer. As Crabb details, a number of opportunities arose but the chance to carry out the deed was somehow missed. Eventually Crabb met Custer and his family – and somehow, ‘that old childish idea of assassinating Custer was obviously out.’

Then I bought me a first class ticket on the U.P. to Omaha for one hundred dollars and two dollars a day for a sleeper on top of that, for I was going back to kill George Armstrong Custer in style… Here we was on Market Square in Kansas City, and I was fully intending to find Custer before the week was out and do my duty…. Now as to my revenge against Custer. Well you can go to the history books and read how he died fighting Indians on June 25, 1876, so you know I never killed him in Kansas City. (Berger, Little Big Man, P204-206).

Eventually Crabb became a look out solider for Custer – and that’s how Crabb ended up at Greasy Grass. Hence Crabb witnessed at close had the demise of this all American hero which Crabb knew instead as a soldier who desired annihilation of the Indians. There’s no doubt Custer held a view the indigenous population had no future – an ethnic society whose main form of communication, as noted earlier, was sign language.

Today General Custer is basically viewed as an ‘American embarrassment.’ Historians agree11 that Custer was arrogant and a narcissist. He was anxious to be a hero, and in fact took steps to reinvent himself as an Indian fighter in order to elevate his standing. The notion of fame took up a large part of his mind. The Fort Laramie agreement of 1868 established a 26 million-acre reservation for ‘absolute and undisturbed use and occupation’ by the Indians. The Great Sioux Reservation as it was known, designated settler free. The agreement largely failed because the US Government did not honour it – this being partially due to General Custer. In 1874 he had claimed part of the reservation area in question, the Black Hills, contained substantial sources of gold.12 John Wild, a trooper, had warned people would be disappointed to find there basically was no gold.13 Nevertheless the situation instigated a gold rush – much to the Indians’ chagrin.

Custer’s 1874 incursion to the Black Hills – which was part of the newly agreed reservation. This angered the Indian tribes greatly. Wikipedia.

This utter disregard for the newly negotiated reservation prompted many of the Indian tribes to outright discard the idea of any reservation set aside exclusively for them. It prompted a number of considerable battles in which the US Cavalry attempted to fight and contain the Indians within the new reservation. that largely culminated in that at Little Bighorn. The battle itself has been immortalised in history, books, film and media. The battle field site is today a National Park. The National Park’s website has a detailed Context and Story of the Battle page which illustrates how the scene was set between the signing of the Fort Laramie agreement and Little Bighorn itself.

In 1876 Custer was hailed as a hero who had bravely died in battle against the Natives. Today we know different:

Idealized in the Budweiser promotional lithograph that once decorated the nation’s saloons, restaged to gallant or belittling effect in too many movies to count, the prairie Götterdämmerung we know as ‘Custer’s Last Stand’ has endured, above all, as an iconic American image. Today, Custer has long since become an embarrassment to educated white Americans. But the effort we’ve put into debunking him amounts to admitting we’re stuck with him…. Unsurprisingly, the Custer literature is huge. An online search tosses up almost twice as many titles as there are books on the Titanic’s sinking — another shock, as Philbrick notes, that also caused a society ‘drunk on its own potency and power’ to ‘wonder how this could have happened.’14

Custer gets killed. Dustin Hoffman, Richard Mulligan in the 1970 film Little Big Man. Some of the battle scenes were actually filmed at Little Bighorn itself. Youtube.

In terms of Jack Crabb, we know no such person witnessed Custer’s last stand. The person who in fact had witnessed Custer’s demise was a woman. A few Indian women were allowed to do battle, this was largely a means of revenge against those cavalry men who undertook awful atrocities against women and children in the natives’ villages. Buffalo Calf Road Woman of the Northern Cheyenne fought against the whites in order to protect her family and her entire people. She is said to have been the one who killed Custer.

George Custer was notorious for attacking encampments of unarmed women and children. So, it’s only befitting that a Cheyenne, Buffalo Calf Road Woman, is credited with killing him at the Battle of Little Bighorn, June 25th, 1876. pic.twitter.com/J81Y3OYgnH

— Lakota Man (@LakotaMan1) June 25, 2023

Buffalo Calf Road Woman – credited with Custer’s demise. Also see part of this Reddit discussion.

Besides Buffalo Calf Road Woman, at least four others are known to have fought against Custer. These are Pretty Nose, Moving Robe Woman, Minnie Hollow Wood and One Who Walks with the Stars.

In terms of Greasy Grass (Little Big Horn) its quite evident the American Indians had exacted a long awaited revenge upon the white imperialist setters. Custer was of course the settler’s highly esteemed mascot and this is why he had to be brought down.

And yet the struggles continued after Little Big Horn. The whites sought every avenue possible in order to impose their occluded world-view upon the American natives. This endeavour too paralleled the plight facing another community – that of the Deaf. The interesting thing about both is they were substantial users of sign language. The American Indians spoke of course, but they used sign language as their main means of communication between the different tribes/dialects. Besides, sign language was something that wasn’t greatly approved by the white settlers anyway. Sign language very clearly stood in the way of the white settlers’ progress across the American continent, therefore those using it had to be removed whether they liked it or not.

As for Custer’s worldview of the American West and its Native Indian occupants, and why it led to Little Big Horn, that’s something we will find out more about in the next instalments of this series.

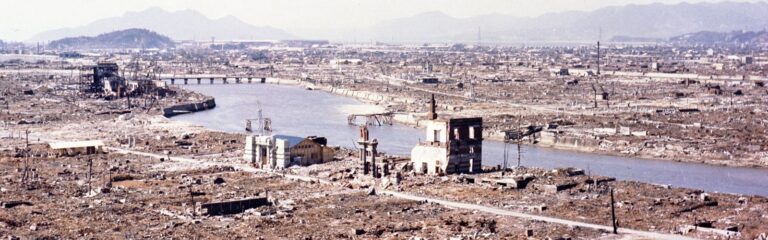

The feature image is of Little Big Man’s shirt sourced from the 9th Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology 1887-88, a copy of which was found on Ebay and cleaned up by Deaf21. This shirt was used by the real life Little Big Man who battled against the US armies including at Little Bighorn.

Bibliography/References

The references to Harlan Lane’s work, When the Mind Hears, (published by Penguin/Pelican Books in 1984) were from the author’s own copy of that book. There appear to be no sources on the Internet that detail these references or quotes.

- Nesterak, M. (2019). Uprooted: the 1950s plan to erase Indian Country. APM Reports. Available at: https://www.apmreports.org/episode/2019/11/01/uprooted-the-1950s-plan-to-erase-indian-country (Accessed: September 2025). ↩︎

- Lane, H. (1992). The Mask of Benevolence. Knopf Publishing Group. Quote seen at Abe Books. https://www.abebooks.co.uk/9780679404620/Mask-Benevolence-Disabling-Deaf-Community-0679404627/plp (Accessed: September 2025) ↩︎

- Mallery, Garrick. (1881). Sign Language among North American Indians. www.gutenberg.org. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/17451/17451-h/17451-h.htm (Accessed: September 2025). ↩︎

- Ditto. ↩︎

- Ditto. ↩︎

- Gibson, C. (2020). Pilgrim fathers: harsh truths amid the Mayflower myths of nationhood. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/sep/20/pilgrim-fathers-harsh-truths-amid-the-mayflower-myths-of-nationhood [Accessed September 2025]. ↩︎

- Equal Justice Initiative (2019). Congress Creates Fund to “Civilize” Native American People. Available at: https://calendar.eji.org/racial-injustice/mar/03 [Accessed September 2025]. ↩︎

- Wikipedia Contributors (2025). Little Big Man (novel). Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Little_Big_Man_(novel). (Accessed: August 2025). ↩︎

- Mishev, D. (2021). North of Yellowstone is the Richest Hill on Earth. [online] Yellowstone National Park. Available at: https://www.yellowstonepark.com/road-trips/road-trip-stops/visit-montana/butte-montana/. (Accessed: August 2025). ↩︎

- Spears, M. (2024) Testing Rail Car on Abandoned Railroad with 100 Year Old Tunnel and Trestles. YouTube. Available at: https://youtu.be/XvbUKqZdtjY?feature=shared (Accessed: August 2025).

↩︎ - Cornwell, A. (2025) General George Custer: A fool, or a misguided narcissist? Our Great American Heritage. Available at: https://www.ourgreatamericanheritage.com/2015/08/general-george-custer-a-fool-or-a-misguided-narcissist/ (Accessed: August 2025).

↩︎ - North Dakota Government. (2025). Custer’s Map – Set 2: Mapping the Land & its People – Unit 1: The Natural World. State Historical Society of North Dakota. Available at: https://www.history.nd.gov/textbook/unit1_natworld/unit1_2_custer.html [Accessed September 2025]. ↩︎

- Shapell. (2023). Black Hills Gold Rush | Shapell Manuscript Foundation. Available at: https://www.shapell.org/manuscript/black-hills-gold-rush-1870s/ [Accessed September 2025]. ↩︎

- Carson, T. (2011) George Custer: An American embarrassment. Salon. Available at: https://www.salon.com/2010/05/07/philbrick_the_last_stand/ (Accessed: August 2025).

↩︎