Did the Deaf help Bell invent the telephone?

Howard Glyndon is, for the better versed of those who have studied Deaf history, an American woman who has a town named after her. Laura Redden Searing, a noted journalist during the time of the American Civil War, was profoundly Deaf and in her quest to better work with hearing people, she decided it was important to learn some speech. Who better to seek for help than the one and only Alexander Graham Bell? I mean, he was the very person who wanted the Deaf to be shot of sign language and to become fully ‘hearing’ with an articulate use of speech. Bell was a person who expected no less than the moon from the Deaf community and for them to accept their fate – lock, stock and barrel.

This quest ensued in the days before Bell had any notion of inventing the telephone. Its an interesting story but its by no means one that supports Bell comprehensively in how the telephone was fashioned. The first, and perhaps most important point is Bell has been considerably discredited – having stolen the idea for the telephone from an Italian inventor by the name of Antonio Meucci. So that puts a considerable damper on anyone who might like to celebrate Bell as an inventor.

As for being a hero, well Bell might be that to some – but for many Deaf people he isn’t even any sort of hero but rather what can only be considered an overbearing evil.

The name Glyndon (aka Redden) pops up quite often in research and the following accounts are what happens to be a barely documented part of her life. Thus it was thought there should be some mention of this aspect because historical books have missed it out altogether (or are probably not aware of it even).

Aside from the historical grab of the rights to possible claim of having first invented the telephone is this Bell/Glyndon collab a true story even? Well it does appear it has some truth to it, and since it was evidently written by Laura Redden Searing herself, there’s little reason to to see it as being inauthentic.

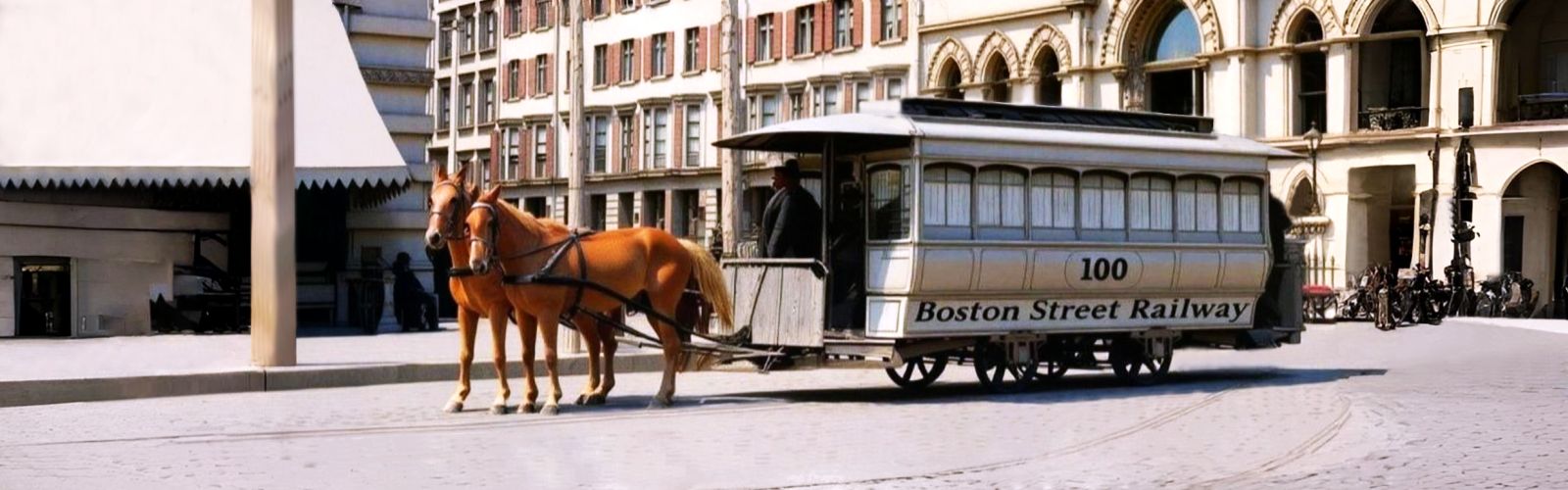

Bell had notions of creating a device to help the Deaf to hear, mainly because his mother was Deaf. He however started developing what would be seen as an advanced telegraph device once he had moved to Boston. This device would supersede the existing telegraph systems. No doubt the work eventually developed into the telephone and according to the following accounts that occurred because of the Deaf feeling the vibrations from Boston’s horse drawn street cars.

Nevertheless, the question does remain as to who had been the original telephone inventor. Had it been Meucci? Or Elisha Gray even? Its a matter that’s still this day open to debate. Boston is where the Glyndon story is said to have occurred in 1872. Curiously 1872 is also the year Meucci had encouraged the Western Union Company to test his prototype telephone system. Thus Bell was not even anywhere near inventing the telephone.

Ironically it was Gray, while working for Western Union in 1874, who was the one that informed Meucci his valuable prototype telephones had been irretrievably lost. It was Bell who edged both Gray and Meucci out of the race by registering the first fully detailed telephone designs at the U.S. Patents Office. Even in those early days it was strongly suspected Bell had committed fraud in placing those first telephone patents. The numerous legal battles of the time eventually decreed that Bell had been the inventor of the telephone. And yet that too remained unresolved until the US decreed it had been Meucci rather than Bell who should be credited with the telephone’s invention.

To this day the debate rages on with various parties trying to advocate Bell, Gray or even Meucci as the rightful inventor. There’s no doubt whomever had been the rightful inventor of the telephone does hold some interest, but in terms of the ongoing controversy, I simply have no desire to sort the wheat form the chaff. In retrospect I would think Meucci deserved the credit, but then a device that has been of enormous benefit to the hearing – and doubly used as a tool to discredit the Deaf massively isn’t something I wish to dwell too much upon.

It seems Bell was trying to ride on the backs of everyone else in order to be the first with his invention. Evidently he did the same with the Deaf too. If it had not been for his mother being Deaf or his wife also being Deaf, the telephone might have not been invented in the way it had, and there would have been no opportunity for Bell to extol the explicit evils he would later espouse, such as advocating the prevention of a Deaf race, ensuring that sign language was banned, and also advocating were clearly eugenicist and racist ideology.

The Glyndon/Redden connection is interesting because it implies a considerable factor in the development of the telephone. Its said that Laura Redden Searing gave Bell some new ideas upon which he could establish a better working of the telephone system he had in mind. Essentially it was the vibrations that could be felt from the traffic (this being the horse drawn street cars) that caused her to have some sensations in her winter muffs and she duly reported these to Bell. Horse drawn street cars first began in Boston during 1856 thus by 1872 a quite considerable system had developed and there’s no doubt a Deaf person would have felt the vibrations in the road surface made by what were undoubtedly a very heavy form of transport.

Clearly these Victorian muffs were more than just a wrap round for a woman’s hands. Sometimes a small hot water bottle was also used and these were made from metal. There’s no doubt the metal bottle would have amplified any vibrations from the horse drawn trams as they clattered over the rail joints or switches. Not only that, the horses hooves, being furnished with iron shoes, would also cause vibrations too.

Thus in a sense it was the notion of a muff with a metal implement within that gave Bell the idea for a device involving a sensor of some sort located within a circular casing of some kind. Initially the design was intended for use as a warning device for the Deaf. This, a box that acted as a sound conductor was soon developed as the telephone. If it had been the Deaf who inadvertently helped Bell with his inventions, there can be no doubt a cruel irony had been enacted.

The Deaf have known what a most cruel and unfair invention the telephone has been. It has constantly been used as an excuse why Deaf people can’t have jobs or even get promotion at work. The telephone has been used as a constant excuse to push the Deaf to the back of the opportunities queue and to keep them there. No wonder Deaf people are angry.

Let’s forget the insensitivities the telephone had caused for a moment and consider what is an account of the events that occurred during 1872. The following account was written in 1885 and first published across a number of Scottish newspapers on the 11th July 1885 – including the Paisley and Renfrewshire Gazette and the North British Advertiser. The Scottish newspapers were most happy to publish this story because Bell was a Scotsman. So they were hailing Bell for he was one of their country’s major heroes. For some strange reason however the newspapers decided that Howard Glyndon was male. Perhaps they read the drafts wrong or decided it just was not possible for a woman to pen under the aegis of being male. Some other newspapers later published a shorter account of these events, but at least they do say she was female and in several instances her real name is also given.

One other fact must be mentioned. It wasn’t just women, but also men who wore muffs and they also utilised hot water bottles to warm up their muffs. Thus a male character wearing fur covered heated muffs would have not seemed out of place to anyone.

Anyway, we start with the full and comprehensive Howard Glyndon story – because its the one that conveys the most detail in terms of what appears to be an unknown history:

THE STORY OF A YOUNG SCOTSMAN’S GREAT INVENTION.

Mr. Howard Glyndon, a deaf-mute, favours us with a graphic sketch of that son of the old teacher of elocution in Edinburgh, Mr. Melville Bell, who has become famous in both hemispheres as the inventor of the telephone. It was in 1872 that Mr. Glyndon first met Alexander Graham Bell, at that time a tall, slim, young Scotsman, giving evidences of his descent from a scholarly family. Although not exactly fragile, he was narrow-chested, and his father had removed from London to Ontario solely on account of his anxiety about the health of this, his only surviving son, all the others having died on reaching manhood from lung disease.From Canada young Bell passed over to the United States by invitation to teach his father’s system of ‘Visible Speech’ to the instructors of the deaf and dumb in various articulation schools. Mr. Glyndon was a private pupil of his in Boston, where he settled for a time, and where he had a small private school, which he called ‘An Establishment for the Study of Vocal Physiology, for the correction of stammering and other defects of utterance, and for practical instruction in visible speech.’

In conjunction with others, Mr. Bell later on founded ‘a University of Elocution’ in Boston. Though at that time not over twenty-four, his education had been very thorough and diverse, the greater part of it received at Edinburgh University, and the most of his leisure time was spent in scientific experiments. The transmission of sound had interested him before he came to the United States, and daily occurrences in the school-room kept his mind upon that subject.

The germ of the idea which culminated in the telephone is conjectured by Mr. Glyndon to have sprung from the following incident :- One or more of Mr. Bell’s pupils, including Mr. Glyndon, and two or three outsiders, were assembled in his sitting-room one winter night, and Mr. Glyndon related an experience which had befallen him that afternoon. He was out for a constitutional in a much-frequented and broad avenue, up and down which street cars were running. The air was crisp and frosty; and as he walked briskly on, holding his hands in his muff pressed closely to his cheat, his attention was several times drawn to a peculiar metallic vibration in the air.

He noticed that this occurred only if, when a car was passing, he held his muff closely pressed to his body and in front of him. He concluded that what he felt was caused by the passing of the wheels of the cars over the iron rails, the vibration of which, by some peculiar property of the atmosphere-the conditions in himself being also favourable-were transmitted to his intelligence through his chest. He has never since experienced the same sensations.

It was a sort of not un-musical singing or humming of the air. When he was told about this, Mr. Bell at once began some experiments upon those who were deaf, expressing his belief that a sort of instrument – a sound-box, he called it – could be constructed for the use of the deaf, which could be carried by them while abroad, concealed in their outer garments in front of them, where sound is most likely to strike a deaf person.

This was for the purpose of enabling them to get out of the way of vehicles that might be approaching unseen. He immediately began to search for material out of which to construct such a box, which would give it the highest power as a sound-conductor. He made several boxes of different materials, including one covered like a drumhead, and he experimented upon his deaf pupils. This went on for several weeks, when finally the sound-box was thrown aside.

‘We heard no more of it,’ says Mr. Glyndon, ‘and I understood from a few mysterious utterances that he had stumbled upon a new idea in connection with it, which was to be of great value to the world at large. I knew that he was working on some sort of a machine; and we two deaf pupils were still made the subjects of experiments. But, whatever he had in his mind, he was very anxious to keep it secret; and as the invention progressed, he became quite excited, be- cause he had no place where be could work in private – he could not even lock it up.

He was then only a young teacher, almost a stranger, and almost friendless in Boston. He was dependent entirely on the proceeds of tuition, and had no money to ‘spare for experiments. One afternoon I met him in a second-hand furniture store, and he explained that he was looking for a small inexpensive stand on which to place his precious invention, so that he could work at it with more ease. The next day I saw the unfinished machine on a small stand in his reception-room. It had a cloth thrown over it. But soon he saw it would not do to leave it in that exposed position, for some one who could understand the principle of his invention might call in his absence, and in an idle moment investigate it, and in some way his idea might be stolen from him before he could perfect and patent it. So one day, on coming in, I saw the top of the table covered with a case like that of a sewing machine. It was secured with a look; and after that be always kept the cover on and locked when he wasn’t at work.

His experiments, started in the winter of 1872-3, extended into the next summer, and were still going on when I left Boston late in the summer of 1873. Sometimes he would appear to be baffled and lay the invention aside. Then again be would have spells of working on it, when he would work all night, and perhaps for several nights running, if one might judge from his fatigued appearance. He spoke to me Occasionally of what he was doing, but always in a mysterious manner. It was about one year after this that the telephone was first publicly mentioned.’

In any event it is obvious that the description of Howard Glyndon as a he is quite wrong for it was a woman. Sometime later a number of shorter articles were repeated across newspapers throughout the British isles and these very clearly divulge that the Howard Glyndon in question was Laura Redden Searing. These shorter articles were repeated in many newspapers throughout 1885 until 1887 or thereabouts. One example of that shorter article is shown below. It was repeated in a similar format throughout the many newspapers it was published:

From the Ulverston Mirror and Furness Reflector 25th July 1885. The full text is repeated below.

HOW THE TELEPHONE CAME INTO EXISTENCE.

The American lady who writes under the pseudonym of “Howard Glyndon” has recently written an interesting account of Professor Graham Bell and his invention of the telephone. Mrs. Laura Redden – for that is her name – made his acquaintance in 1872, when she was one of the deaf pupils to whom be taught articulation on the basis of the “Visible Speech” invented by his father, Melville Bell. He had at that time a small “Establishment for the Study of Vocal Physiology, for the Correction of Stammering and other Defects of Utterance and for Practical instruction in Visible Speech.”“Howard Glyndon” soon noticed that the tall, slim, narrow-chested young Scotchman was interested in scientific experiments, especially in such as had relation to the transmission of sound:- Perhaps (she observes) the germ of the idea which culminated in the telephone sprang from the following incident:- One or more of his pupils, borides myself and perhaps two or three outsiders, were assembled in his sitting-room one winter evening, and I related an experience which had befallen me that afternoon. I was out for a constitutional on a much-frequented and broad avenue, up and down which street cars were running.

The air was crisp and frosty, and as I walked briskly on holding my hands in my muff pressed closely to my chest my attention was several times drawn to a peculiar metallic vibration in the air; and I noticed that this occurred only if when a street car was passing I held my muff closely pressed to my body and in front of me. I concluded that what I felt was caused by the passing of the wheels of the cars over the iron rails, the vibrations of which by some peculiar property of the atmosphere – the conditions in myself being also favourable – were transmitted to my intelligence through my chest. I, however, have never since experienced the same sensations. It was a sort of not un-musical singing or humming of the air.

Professor Graham Bell immediately began to experiment with the view of devising “sound-boxes” which “Howard Glyndon” and his other deaf pupils might carry in front of them concealed in the folds of their outer garments, and which would give sufficient warning of approaching vehicles to enable them to escape. After some weeks of work this was abandoned, but the pupils had hints that Mr. Bell had “stumbled upon a new idea in connection with it which was to be of great value to the world at large.” He continued to experiment, and the schoolroom had in a corner a mysterious looking contrivance which was covered over like the top of a sewing machine from too inquisitive eyes. He had the hot fits and the cold fits of an inventor; was sometimes ready to give up in despair; and sometimes worked through the hours that should have been devoted to sleep. Finally the thing was done, and the telephone became a scientific fact.