Jean Massieu and the thief

In what was a long period of war and conflict that had begun in 1792, France declared itself a country in danger (‘Citoyens, La Patrie est en danger‘) due to the wars that had begun with Austria, Britain, the Dutch, Prussia, Russia, Spain and others. Essentially it was those countries with monarchies that were pitted against France. The French no doubt had a lot on their hands for it was also experiencing a revolution within, having deposed its own king. Those tumultuous years began in July 1789 with the storming of the Bastille. Its why France and other countries celebrate Bastille Day. The year 1792 also saw the publication of a book of considerable significance – ‘Les Crimes des Rois de France‘ (this followed the earlier Les Crimes des Reines de France). Both books illustrated what were said to be numerous misdeeds by the Royals. September 1792 saw France become a Republic and it would not be long before both King and Queen were shown the guillotine.

Another certain event also occurred in 1792 and this particularly involved the Deaf. Although it wasn’t seen as perhaps anything beyond the norm, in a sense it was radical, revolutionary even, because the victim, a noted Deaf man, chose to not follow the rest of society in its way of how criminals ought to be treated. it The period concerning what was no doubt a hearing thief occurred in either late June or early July 1792 – this was around the time France had declared itself in danger. Even then some days in Paris somehow managed to keep a normal semblance despite the ongoing chaos. The day in question was one of those when a group of Deaf happened to come across a ceremony to celebrate the Blessed Sacrament. This was likely because during 1792, as part of the Revolution’s dechristianization attempts, religious processions were being suppressed or had already ceased, thus the procession was perhaps a protest of sorts.

The main figure in all this in terms of the Deaf would have been the Abbé Sicard. As history shows, he was an important figure in terms of how the Deaf world would progress over the next century or so. The Abbé very clearly desired a continuation of the work undertaken by his predecessor, the Abbé de l’Épée. This work was developed to an even greater degree and the modus was intended to give the Deaf greater empowerment and knowledge by way of a more comprehensive utilisation of sign language. This was seen as a far better system than the oralist method of teaching the Deaf to speak.

Even invigilators of Deaf education such as the Abbé Sicard fell foul of the violent on goings in the French capital and he was lucky to escape with his life during the killing of numerous religious figures in early September 1792. These were part of what is known as the September Massacres. See below for the English translation of the above text. Wikipedia.

The former Abbé Sicard. He was denounced as a moderate by a Revolutionary Committee, arrested, and forcibly imprisoned. On September 2nd and 3rd, he was included without examination among the crowd of victims destined to perish in those fatal days. Arms were already raised to strike him; when Citizen Monot, the watchmaker, rushed forward! He covered him with his body, crying out, “Stop! Friends, what shall we do?… It’s Citizen Sicard! He who makes the mute speak and the deaf hear… Strike me if you will, but spare this vulnerable man…” At these words, the fury of the would-be assassins turned to benevolence. They took in their arms the one they were about to strike and carried him home, shouting, “Long live Sicard!”

He is described as the ‘former Abbé Sicard’ because he was defrocked at some point prior to the incidents of September 1792. This was a result of France’s Dechristianisation policies. Sicard had in fact been rounded up with many other clergy (including abbots) and imprisoned at the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris during 2nd and 3rd September 1792 (according to a report written in the Anti Gallican Monitor for 22nd January 1815) pending execution. No doubt when things had quietened down, perhaps at some period after 1800 Sicard’s religious honour was restored. Initially he ran the Paris school for perhaps eight years or more as as a mere citizen rather than the Abbott he was renowned. It was only as ‘Citizen Sicard’ the revolutionary French would indeed permit him to have ‘all the leisure and all the freedom he needs to pursue his useful work.’ 1

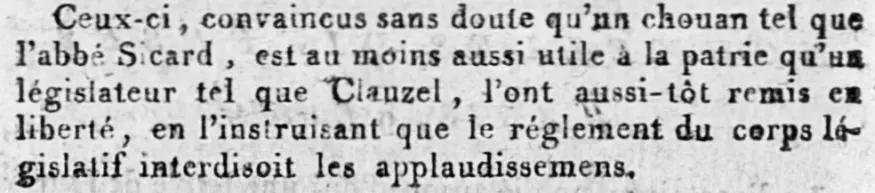

Sicard was mentioned a number of times in a number of revolutionary publications (besides the Vedette, the Abbé was also reported in the Courier du Jour, Le Véridique ou Courrier Universel, Le Publiciste, the Journal de Francfort, Le Narrateur Universel and others). This because he was seen as a Chouannerie. As a member of the Clergy the Abbé was to all intents on the wrong side even though he greatly sympathised with the aims of the revolution.

The Abbé Sicard is reported as a chouan (Chouannerie).2

The Abbe Sicard’s life during these problematic times must have been extremely uncertain. In terms of Deaf history it is therefore somewhat comforting because even though an attempted theft had been made, the event of its being reported had quite likely helped to save the Abbé’s life. Hence that too enabled the manualists’ survival. Had the Abbé not been saved, well there’s absolutely no knowing what could have happened but more likely that the oralists would have found an easier road in terms of debasing the manual system of learning and forcing fully assimilation in to the hearing world. As it stands, the revolutionaries in fact acknowledged Citizen Sicard as one of the great creators of sign language – and they gave him full dispensation in his work by granting him the right to manage the first school for the Deaf in Paris.

The focus of this article is an event which happens to be a little known chapter in the life of the Deaf educator – Jean Massieu. The incident occurred in the days before he became well known as a stoic supporter of the right of the deaf-mute to be educated in sign language. This was when both the Abbé Sicard and Massieu worked together to elevate the situation of the Deaf. Massieu had originally been a student of Sicard’s as early as 1785 at Sicard’s school in Bordeaux, and by 1792, Massieu was working as a teacher of the Deaf. Six years later he would be chief teaching assistant at the Institution Nationale des Sourds-Muets à Paris under the instruction of the Abbé Sicard. Below is a painting of Massieu with the Abbe Sicard at the school.

Jean Massieu (at left) and the Abbé Sicard with some of the Paris school’s pupils in 1806. Facebook.

Jean Massieu and the thief – July 1792.

It must be mentioned that Laurent Clerc has written about this aspect of Massieu’s life previously in his biography of Massieu. Here’s that to start with. Anyone who has read of the incident will have most likely read of it in the relevant American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb – which is available at Gallaudet/JStor. Clerc does not give any idea of when the incident had occurred – however its clear it took place during the summer of 1792.

Massieu was an important figure in the life of the Abbé Sicard, therefore it seems that perhaps is a reason why Massieu also received occasional mention in the revolutionary newspapers of the time. A couple of examples can be seen in Le Publiciste (14 September 1800) 3 and another (30 September 1800).4 These stories of the thief appears to be from one in particular which is the Vedette ou Gazette du Jour – the edition in question doesn’t seem to be online.

As for the thief in question – there’s no doubt he was hearing. Basically what it amounts to is Massieu was Deaf and he had to face not only a crime by a hearing person but also a judicial system (and a pretty messy chaos too) that was managed by hearing people. In spite of those odds Massieu clearly managed to ensure his philosophy on life would seek to prevent the usual sort of stance that was given to criminals. To put it differently, it appears Massieu didn’t want to see the murderous ways of the current hearing society employed as a means of justice. As a Deaf person that is just my assumption. Anyway here is the passage referencing this theft. Its from the American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb and was written by Laurent Clerc: 5

One day he had a complaint to make against a man who had attempted to rob him of his pocket-book. He repaired to one of the Paris police-offices, and demanded a sheet of paper and wrote as follows:

Mr. Judge, I am deaf and dumb. I was looking at some- thing in a broad street with other deaf and dumb persons. This man saw me. He noticed a small pocket-book in the pocket of my coat. He slily approached me. He was drawing out the pocket-book when my hip warned me. I turned myself briskly towards this man, who being afraid, threw the pocket-book between the legs of another man, who picked it up and returned it to me. I seized the thief by his jacket, I held him fast; he became pale and trembling. I beckoned to a police-officer to come. I showed the pocket-book to the officer and expressed to him by signs that that man had stolen my pocket-book. The officer brought the thief hither. I have followed him. I demand justice. I swear before God that he stole this pocket-book from me. He, I dare say, will not deny the fact. I beg you, Mr. Judge, not to order him to be beheaded; he has not killed any one, but let him be reprimanded and I will be satisfied.

The thief was convicted and sentenced to imprisonment for three months in the jail of Bicetre.

The ‘jail of Bicêtre’ is the former hospital in the south of Paris which has been used as an orphanage, an asylum and a prison.6 Today it is a major hospital.7

I have not seen the original source of this anywhere until it was actually offered as a document for sale on Ebay. The seller probably had little idea of its historical significance – indeed he probably thought the document less valuable that it ought to have been. The images of the document were copied and thankfully the passages with Massieu’s experience had been left intact rather than one page or the other page being left out as is usually the case with these Ebay offerings – leaving historians with what is an incomplete and partial picture.

What is of interest is even though Clerc wrote basically what had went on the overview of the case itself had been left out. Whether Clerc had seen the original article (eg the Vedette ou Gazette du Jour) or not is of course something that must be taken into consideration. Nevertheless the article’s conclusion is of interest because it shows even despite the incident that had occurred the author still expressed a surprise that a deaf and dumb man had done what he did – which was to make a case for the thief to be thrown into jail rather than face a beheading. In those days (even in England) thieves could be beheaded. The surprise expressed was that a deaf and dumb man had the intelligence to see to it that a different punishment was meted out.

In a sense it exposes the classical overview hearing society generally had of the Deaf – that they were dull, unintelligent, illiberal, and not worthy of education.

The Vedette ou Gazette du Jour (The Daily Featured News) was part of a collection of newspapers/journals published during the French Revolution and representing both sides of the conflict. A substantial part of those can be found at the University of Kentucky – however the publication in question does not seem to be part of that particular archive.

The report in the Vedette ou Gazette du Jour may have possibly helped the Abbé Sicard by way of his having ‘restored the deaf-mute to society’. In a sense it can be said that despite the revolution, the value of that was placed above anything the revolutionaries had originally captured the Abbé for in the first place – and that the revolution did not destroy the valuable work the manualists (those who believe in sign language and not speech) had been doing.

The Vedette ou Gazette du Jour for 11 Julliet 1792. Pages five and six containing the passage on Massieu have been combined for readability.

The text is as follows:

Parmi les évènemens qui doivent eutrer dans l’histoire des tribunaux, on doit ranger, fans doute, la cause portée au tribunal de police correctionnelle de Paris, par Jean Massieu, sourd & muet, âgé de 19 ans, plaignant contre un voleur qui lui avoit escroqué son porte-feuille. Ce sourd & muet, marif de Bordeaux, élève de l’abbé Sicard, sans être accompagné d’aucun défenseur, se rend au tribunal, & en présence du magistat, il écrit sa plainte dans les termes fuivans.

Jean Massieu, à son juge:

Monsieur, je suis sourd-muet: j’étais regardant le soleil du Saint-Sacrement, dans une grande rue, avec tous les autres sourds-muets. Cet homme m’a vu : il a vu un petit porte-feuille rouge dans la poche droite de mon habit. Il s’approche doucement de moi, il prend ce porte-feuille. Mon hanche m’avertit: je me tourne vivement vers cet homme qui a peur. Il jette le porte-feuille sur la jambe d’un autre homme qui le ramasse & me le rend. Je prends l’homme voleur par sa veste ; je le retiens fortement, il devient pâle, blême & tremblant. Je fais signe à un soldat de venir. Je montre le porte-feuille au soldat, en lui faisant signe que cet homme a volé mon porte-feuille. Le foldat prend l’homme voleur, & le mène ici. Je l’ai suivi. Je vous demande de nous juger. Je jure Dieu qu’il mat volé ce porte-feuille. Lui, n’osera pas jure Dieu. « Je vous prie de ne pas ordonner de le décapiter: il n’a pas tué; mais feulement dites qu’on le fasse ramer.

Après la lecture de cette pièce, on se demandera peut être quel est le plus admirable du sourd-muet rendu à la société, ou de l’être intelligent qui, par une suite de découvertes & de procédés ingénieux, est parvenu à développer, dans cette statue animée, la raison que le défaut d’un sens y tenoit captive. De tous temps il a existé des sourds-muets; de tout temps ces malheureux ont été le rebut de la société dont ils étoient séparés par un intervalle immense. L’abbé de l’Epée feul a commencé, & l’abbé Sicard a achevé de combler cet intervalle.

The above is evidently old French with a number of words that don’t exist or have a different meaning these days. What follows is the translation in English. Several translation engines were used and then also grammar check and because some of it didn’t make sense. The last paragraph made little sense in its totality, especially the first sentence with ‘dans cette statue animée, la raison que le défaut d’un sens y tenoit captive’. (There’s no such word as tenoit and tenoir doesn’t fit either according to grammar engines). That had to be changed because there isn’t a proper translation of that passage. The best has been done of this mish-mash of words – however the art of French is not even a skill Deaf21 has thus it was hugely problematic to work out what the translation and context ought to be.

Anyway here’s the English translation. It may not be absolutely correct but its done the best it can be:

Among the events that must be recorded in the history of the courts, one must undoubtedly include the case brought before the correctional police court of Paris by Jean Massieu, a deaf and mute man, aged 19, complaining of a thief who had stolen his wallet. This deaf and mute man, a student of Abbé Sicard, went to the court without being accompanied by an attorney and in the presence of the magistrate, he wrote his complaint as follows.

Jean Massieu confers with the judge thus:

Sir, I am deaf-mute: I was watching the sun of the Blessed Sacrament, in a big street, with all the other deaf-mutes. This man saw me: he saw a small red wallet in the right pocket of my coat. He slowly approaches me, he takes that wallet. My hip warns me: I turn sharply towards this man who is scared. He throws the wallet onto the leg of another man who picks it up and returns it to me. I grab the thief by his jacket; I hold him tightly, he turns pale, ashen, and trembling. I signal to a soldier to come. I show the wallet to the soldier, signalling to him that this man stole my wallet. The soldier takes the thief, and leads him here. I followed him. I ask you to judge us. I swear to God he stole that wallet. He, he won’t dare swear to God. “I beg you not to order his beheading; he did not kill; but only say that he be whipped.”

The conversation was conducted by way of communication on written paper – a system which many in the hearing world disregarded as being primitive. One wonders whether the judge doubted Massieu’s ability to profess a situation on certain morals – and not to follow the rest of society like sheep and condone an execution as the due punishment. The second part of it – the observation that was made – presumably by the publishers of the Vedette ou Gazette, is somewhat problematic in terms of translation. It seems translation engines can’t make proper sense of it for a couple of those gave up trying! Anyway here it is:

After reading this piece, one might wonder which is more admirable: the deaf-mute brought into society, or the intelligent being who, through a series of discoveries and ingenious processes, has managed to develop, in this animated statue, the reason that the lack of a sense held captive there. Since time immemorial, there have been deaf-mutes; since time immemorial, these unfortunate individuals have been the outcasts of society, from which they were separated by an immense gap. Only the Abbé de l’Épée began, and the Abbé Sicard finished, filling this gap.

What the report seems to be saying (in my estimation) is its expressing interest that even though deaf-mutes are have long been the scourge of society, there is nevertheless a surprise a deaf-mute would rather see to it a thief (who evidently was hearing and had intellect – this being the classic view that those with speech were intelligent whilst those without were unintelligent) be made to suffer the wrong doing of his ways – and for that sufferance to be directed by a deaf and dumb man of all people. In a sense the general overtone of the paragraph appears to be the surprise that a deaf-dumb man could even express an intelligence.

To explain it a little more differently, when animated statue (dans cette statue animée) is cited it clearly means animated state. This in fact refers to Massieu’s state of being Deaf. Then the reason that the lack of a sense held captive there (la raison que le défaut d’un sens y tenoit captive) clearly means Massieu (as a deaf-mute) had a lack of sense, which was no doubt elevated to a more certain intelligence by way of a flood of discoveries and ingenious processes.

This ‘surprise’ is a classic of the oralist/audist tradition. Speech is no doubt a supremacy, and those without that or hearing are indeed ‘dumb’ (no doubt even these days society continues to use that term to such an egregious extent without realising its oppressive and practically racist connotations) its that for a deaf and dumb man to trounce the common view held was amazing – and that because the article’s writer had held a view it simply could not be possible for deaf mutes to express such intelligence. Even so the oralists like to think that it somehow demonstrates that speech is a superior intelligence and there simply is no reason for sign language to even have any continued purpose.

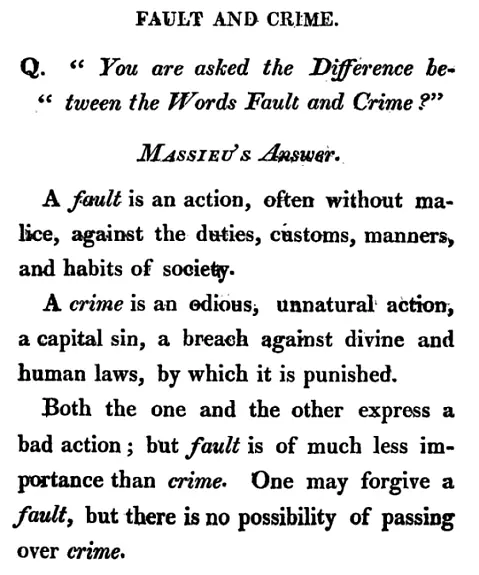

In 1792, and by the age of 19, Jean Massieu already had a different view of things compared to others. In 1815 when Massieu visited England he was asked numerous questions on his outlook pertaining to Government, religion, rights, wrongs, morals, and so on – and a number of the answers are surprisingly modern. Here’s his view on crime:

Image of Massieu’s answer from A collection of the most remarkable definitions and answers of Massieu and Clerc, Deaf and Dumb, to the various questions put to them, at the public lectures of the Abbé Sicard in London (1815).8

Fault and Crime.

Q. “You are asked the Difference between the Words Fault and Crime?”

Massieu’s Answer.

A fault is an action, often without malice, against the duties, customs, manners, and habits of society.

A crime is an odious, unnatural action, a capital sin, a breach against divine and human laws, by which it is punished.

Both the one and the other express a bad action; but fault is of much less importance than crime. One may forgive a fault, but there is no possibility of passing over crime.

A further incident occurred in the summer of 1807 when another theft was conducted against Jean Massieu. (This was reported in several newspapers including the Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette for 11th June 1807). This time it was the Abbé Sicard who provided the interpretation in the Paris court. One of the interesting things on that particular event is the assumption that Massieu was going to tell lies, but no that was not the case, for once again, Massieu maintained his integrity and stuck to the truth.

- University of Kentucky. (2025). Le Publiciste [14 September 1800]. Available at: https://exploreuk.uky.edu/catalog/xt737p8tf45h?q=massieu&f%5Bsource_s%5D%5B%5D=French+Revolution+publications&per_page=20 [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- University of Kentucky. (2025). Le Véridique ou Courrier Universel, 27 August 1796. Available at: https://exploreuk.uky.edu/catalog/xt7n5t3g230p#page/2/mode/1up [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- University of Kentucky. (2025). Le Publiciste [14 September 1800]. Available at: https://exploreuk.uky.edu/catalog/xt737p8tf45h?q=massieu&f%5Bsource_s%5D%5B%5D=French+Revolution+publications&per_page=20 [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- University of Kentucky. (2025). Le Publiciste [30 September 1800]. Available at: https://exploreuk.uky.edu/catalog/xt7qv97zq012?q=massieu&f%5Bsource_s%5D%5B%5D=French+Revolution+publications&per_page=20#page/2/mode/1up [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- CLERC, L. (1849). JEAN MASSIEU. American Annals of the Deaf and Dumb, January 1849, pp.84–89. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/44401132?seq=1 [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- Wikipedia Contributors (2023). Bicêtre Hospital. Wikipedia. Available at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bic%C3%AAtre_Hospital [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- Hôpital Bicêtre. (2016). Hôpital Bicêtre. Available at: https://hopital-bicetre.aphp.fr [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

- de, L. and Sievrac, J.H. (1815). Recueil des définitions et réponses les plus remarquables de Massieu et Clerc, sourds-muets, aux diverses questions quileur ont été faites dans les séances publiques de M. l’Abbé Sicard, à Londres : auquel on a joint l’alphabet manuel des sourds-muets, le discours d’ouverture de M. l’Abbé Sicard, et une lettre explicative de sa méthode. Gallaudet University. Available at: https://ida.gallaudet.edu/deaf_rare_books/119 [Accessed November 2025]. ↩︎

Updated 20th November 2025.