Deaf in Burundi – a case of paternalism

This is a very important piece of work in terms of third world countries and the ways and means in which the Deaf in those countries suffer. It parallels the situations described with what is known as paternalism – in this case this being how the hearing world controls the Deaf. Besides the tool of oralism, paternalism is another mechanism largely employed against those who can’t speak or communicate in the way the status quo would prefer everyone to.

This was from a lecture given by Harlan Lane in London on 27th September 1988. Lane is the much vaunted Northeastern University professor who spent much of his life studying and writing about the oppression of the Deaf. His works like When the Mind Hears: A History of the Deaf; The Mask of Benevolence: Disabling the Deaf Community; The People of the Eye: Deaf Ethnicity and Ancestry; Journey into the Deaf-World; The Wild Boy of Aveyron have become a celebrated source of facts related to the oppression of the Deaf community.

This 1988 talk revolves around Burundi. The talk is no doubt still relevant in terms of what was discussed because it is an eye opener to how the hearing world has manipulated the Deaf. Its not just in Burundi or any other African country that this occurs. Paternalism pretty much occurs everywhere across the globe because it is largely hearing society that calls the shots.

The tiny African state of Burundi is one of the smallest on the continent. According to Wikipedia Burundi is ‘a direct territorial continuation of a pre-colonial era African state’. In other words it is still considerably undeveloped and there have been struggles between the country’s three main ethnic groups. The country currently is working to progress towards a modern democratic state – but its no easy task because the country is poor, impoverished, and there’s high inflation rates plus a scarcity of currency – and little opportunity for work.

Although this research is from the 1980s, there’s every possibility the Deaf in Burundi have seen little progress. There are two dedicated Deaf schools in the entire country for a population between 60,000 to 136,000. No accurate estimates are known of the true number. The largest Deaf school is at Gisuru in Ruyigi Province, and about 18 miles east of its capital. Even though the current government has sought to improve healthcare greatly with the introduction of a number of new hospitals, that for the Deaf is still poor. However it is slowly progressing and state TV has now begun to include LSB (Burundi sign language) in its broadcasts (Gavi).

Lane’s lecture is important because it does give a degree of understanding the extent of paternalism – or hearing control and oppression – and how this bears upon the Deaf.

The lecture is titled: Paternalism, Deaf People and the Third World. An abstract of that article can be seen here. It appears to be a somewhat different form to the lecture Lane gave in 1988 and is probably a condensed version of that given in Sign Language Studies, Volume 60, Fall 1988 and published by Gallaudet University. Not only that the talk also gives reference to BSL too thus it was adapted for the British series of lectures Lane would give. Even though the RNID is credited the talk in fact took place in one of University College London’s lecture halls. The following text is from the transcript of the talk, a copy of which is in the author’s collection.

Paternalism, Deaf People and the Third World (London 27 September 1988 for the Royal National Institute for the Deaf) by Harlan Lane of Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts.

There are some countries in the world where deaf children are not educated because schools for hearing children will not accept them and there are no special schools for deaf children. One such country is the Republic of Burundi, located in Central Africa, with about 5,000,000 people inhabiting a region about the size of Maryland. Twenty-five years ago, Burundi threw off the yoke of a devastating colonial regime and declared its independence from Belgium.

A decade ago I went to Burundi to examine a boy whom people believed was raised by animals. As it turned out, they were wrong the boy only appeared to be a wild child because he had a brain disease. While I was there, I asked about the lives of deaf people. Nine out of ten people in Burundi live on and farm their own little plots of land scattered over a mountainous countryside that has seen almost no transportation until recently. It was reasonable to think that deaf people have trouble getting together and there is no evidence so far of a common sign language in wide use.

I have been collaborating with the government of Burundi in launching deaf education in their country, not only for the sake of their citizens but also for the sake of all five countries of Francophone Central Africa, where there are an estimated 40,000 deaf children and 100,000 deaf adults and no official instruction of deaf people. A school for deaf children in Burundi could be a model for the entire region. If it were conducted to reflect our latest understanding of deafness, it could be a model, indeed, for the rest of the world.

Over a year ago, I spent some weeks in Burundi meeting hearing and deaf people who could advise me on this undertaking. It was a special joy to meet the Umuvyeyi family with six children, five deaf, and two hearing parents, for they were warm, engaging, and close-knit: they had evolved over the years an elaborate and subtle home sign language which appeared to serve them very well. Mme. Umuvyeyi told me that her husband, a secretary by profession, had never really mastered their home sign, but she and the children used it all the time for all the needs of their everyday life. The youngest deaf child, Claudine, fourteen years old, had also learned signs from American Sign Language in a little school for deaf children run by American missionaries. Claudine’s teacher told me that she was the best student they ever had but, sadly, she could not continue her education since there are no regular schools for deaf children. Claudine and her family stayed on my mind after I returned to America. Some time later, I wrote Mme. Umuvyeyi a long letter in French that I would like to share with you today. The letter begins:

“Dear Mme. Umuvyeyi,

You may be surprised to receive another letter from me, especially when I tell you its purpose: I want you to consider giving up your talented and loving daughter Claudine for some years so she can continue her education, and become the first deaf teacher of deaf people in Burundi.”

I went on to explain that the Burundi government had sent me for two years’ training here a psychologist from the University of Burundi, M. Adolphe Sururu. I have learned much from Adolphe about the struggle and achievements of Africans and he, in turn, has learned much about the struggle and achievements of deaf people. I will remember forever the astonishment on his face when, shortly after his arrival, I introduced him to a highly educated deaf friend of mine, a teacher, who was giving instructions to hearing people in her office. Adolphe later explained his wonderment to me; the very word for ‘deaf’ in Kirundi, ‘ikiragi, contains the prefix ‘iki‘ meaning ‘animal’ that appears in such words as ‘crow’ and ‘owl’ (symbols of sorcery) and in ‘mentally-retarded. A Burundian has difficulty imagining deaf people as teachers.

“That is just what I ask you to imagine,” I wrote to Mme. Umuvyeyi, “for I believe that there can be no successful education of deaf people in Burundi without Claudine and deaf people like her as teachers.”

We have learned the hard way in America, I told her, that hearing people as a group cannot single-handedly, without the involvement of deaf people, educate deaf people successfully. The reason, I believe, is this: when the powerful set out to assist the powerless, when benefactors create institutions to aid beneficiaries, a disease sets in so no good can come of it; the name of that disease in human relationships is paternalism.

I call paternalism a disease because, in the first place, it cannot perceive things as they are. More exactly, “it sees through its own glasses,” as Adolphe said to me, and those glasses are highly distorting. For example, when the Belgians took control of Burundi after the First World War, they found in place a unique and elaborate system of government that had evolved over more than four centuries. This traditional government included the king, the princes of royal blood who shared authority with the regional chiefs, local elders who administered justice, religious authorities, and more. The Belgian colonizers chose to imagine, however, that Burundi society was like their own society ten centuries ago, at an earlier stage of development. This was foolish. After all, the Belgians were not in Europe after the fall of the Roman Empire, they were in equatorial Africa. In feudal Europe, the kings had owned and distributed the land and governed the nobles but this was not true in Burundi. Nor did this European image take account of all the other forces in Burundi government, such as the powerful ritual authorities, whom the Christian Belgians would soon persecute as sacrilegious.

The vision of paternalism is defective, I told Mme. Umuvyeyi, not only because it imposes the familiar on the unfamiliar but also because its perception is self-serving; it sees what it wants to see. The Belgians hoped to find a tightly hierarchical aristocratic society such as theirs had been because they intended to make the king their puppet and rule through him. Likewise, it suited them to see the ‘natives’ as children, for this view confirmed the Africans’ need of Belgian guidance and control. As the Belgian colonists saw it, the Burundians’ actions were clearly immoral, they were evidently uncivilized, but European intervention could raise them up to the status of civilized men and women. And if colonial rule did not bring about a better way of life, well it was the primitive nature of the society, which needed ten more centuries to mature, that was responsible for the failure.

Now, the relation between hearing and deaf people also appears to be paternalistic, I explained in my letter. Hearing paternalism similarly begins with defective perception because it superimposes its image of the familiar world of hearing people on the unfamiliar world of deaf people. Hearing paternalism likewise sees its task as civilizing its charges, restoring deaf people to society. And hearing paternalism likewise fails to understand the structure and values of deaf society. For example, in hearing peoples’ milieu, languages are spoken; since deaf people rarely speak, the hearing professionals have long concluded that deaf people have no language at their command. They overlook the manual languages that deaf people have been using and talking about for centuries.

Faced with the unique languages, cultures and histories of deaf communities, the hearing professionals frequently see only stopped-up ears and a desperate need for their services. A doctor wrote in the Boston Herald recently, “The world of the deaf is a lonely one; it is bleak, humorless, and isolated.” Nothing could be further from the truth, or more insulting to the deaf people of Boston, and America. These falsehoods are disseminated by ignorant, paternalistic, hearing professionals. In an American psychiatric publication I read, “Profound deafness that occurs prior to the acquisition of verbal language is socially and psychiatrically devastating.” A recent British publication says of people profoundly deafened early in childhood, “They require a tremendous amount of support from various agencies… to make the emotional and social adjustment to life.” “Since your children are happy, healthy and productive,” I told Mme. Umuvyeyi, “and not psychiatrically devastated, and since they have never had any agencies to help them make an adjustment to life, you know that the hearing professional people who published these claims are suffering from blind paternalism.”

I thought it important to be very candid with Mme. Umuvyeyi and to acknowledge that the hearing people who control the affairs of deaf children and adults commonly do not know deaf people and do not want to. Since they cannot see deaf people as they really are, they make up imaginary deaf people of their own, in accord with their own experiences and needs. Paternalism deals in such stereotypes. The Belgian colonizers have written of Burundians: “The natives are children… superficial, frivolous, fickle. The chiefs are suspicious, cunning and lazy.” As long as white men had charge of the affairs of the Africans, this is the condescending and demeaning conception of them that reigned in government.

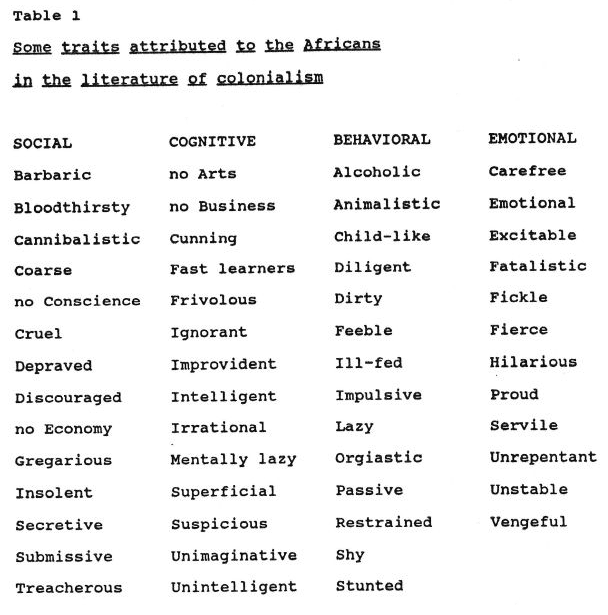

As I have read about Burundi and Africa in general during the past few years, I have kept a list of the characteristics of Africans according to the Europeans who were in charge of them. Here it is, without terms that repeat others, and arranged into four groups. (I have made a tic mark each time the term appeared in my notes.) It is an ugly list. It is, it seems to me, a reflection of the Europeans’ desperate need to impose their will on the Africans and to justify that imposition as civilizing an uncivilized people.

Some traits attributed to the Africans in the literature of colonialism. Harlan Lane 1988.

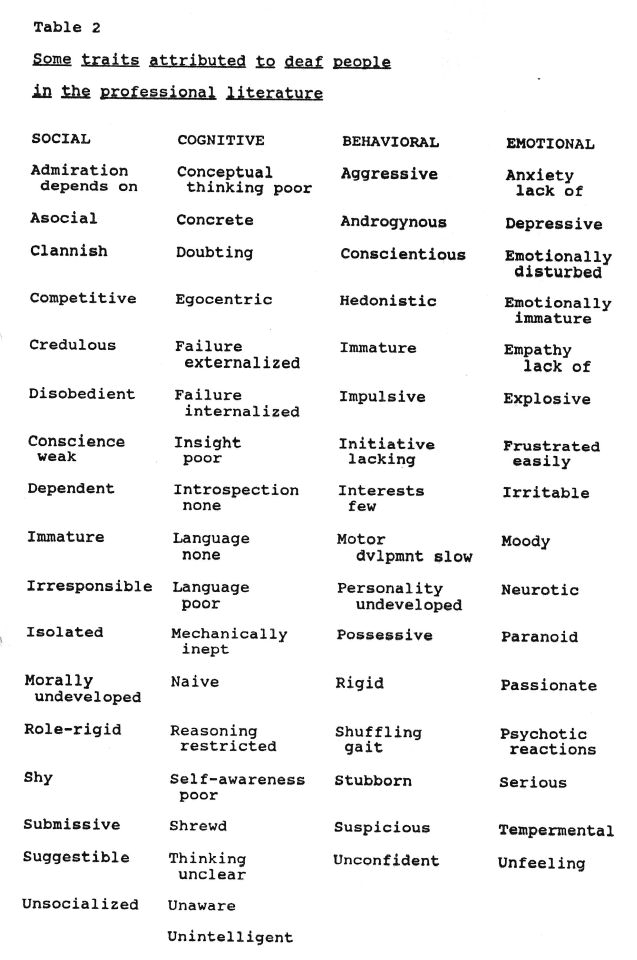

It appears that the same principles of paternalism are at work in hearing relations with deaf people. At my last lecture, I presented a list of the characteristics of deaf people according to the hearing experts in charge of their affairs, who give these descriptions in their professional journals and in their textbooks. It, too, is an ugly list. Let us review it briefly.

The list of traits attributed to deaf people is inconsistent: they are both “aggressive” and “submissive;” “naive/shrewd, detached/passionate, explosive/shy, stubborn/submissive, suspicious/trusting.” The list is, however, consistently negative: nearly all of the traits ascribed, even many in pairs of opposites, are unfavourable. Africans and deaf people appear to have one more thing in common: they are incompetent socially, cognitively, behaviourally, and emotionally.

Some traits attributed to deaf people in the professional literature. Harlan Lane 1988.

The inconsistencies of the trait attributions and their negativity must lead us to suspect that we are dealing in both the “psychology of the native” and the “psychology of the deaf” — not with objective descriptions but with stereotypes. In that case, the trait attributions may reveal little about Africans or deaf people, but much about the colonial authorities or hearing authorities and the social contexts in which they operated.

Many of the traits that hearing authorities attribute to deaf people seem to reflect the struggle of those authorities to impose their will on deaf children or adults. They say, “The deaf have poor social awareness;” they mean, “I wish my deaf pupils or clients would do what hearing people do in this situation.” They say, “The Deaf are isolated;” they mean, “They can’t understand me or other hearing people and they can’t communicate with us.” They say, “These deaf children are disobedient, immature, impulsive;” they mean, “I wish they would do what I tell them to do; it’s hard enough teaching them anything without their disobeying.”

In both cases, Africans and deaf people, there is “an authority that undertakes to supply the needs and regulate the conduct of those under its control” and that is the dictionary definition of paternalism: “a system under which an authority undertakes to supply the needs and regulate the conduct of those under its control.”

But is it accurate to tell Mme. Umuvyeyi that these are not the characteristics of deaf people, that they are instead stereotypes harbored by uninformed paternalistic hearing people?

Let us examine the hypothesis that the relations between hearing and deaf people are essentially paternalistic. If we can think of important characteristics of paternalism, we can test each of them to see if it applies to the relations between the colonizers and the colonized, where we expect it will, and to the relations between hearing and deaf people, the case we want to decide.

The first test, I call a test for paternalistic universals. Despite the very different situations of Burundians at the turn of the century and deaf people in America today, we can predict that the authorities will describe them in many similar ways, because paternalism has certain universal characteristics. For example, benefactors in every place and time tend to perceive their beneficiaries as needing their help. Are there in fact traits common to the two sets of lists traits attributed to the Africans then and to deaf people now? Indeed there are. Here are some traits on both lists: “childlike, shy, submissive, and unintelligent.” For the authorities to call both Africans and deaf people “childlike, shy, submissive, and unintelligent” suggests that the authorities are concerned with justifying their role. The authorities seem to reason that if Africans (or deaf people) were mature, self-assured, assertive, and smart, the authorities wouldn’t be needed. Since the authorities are very much in charge, it stands to reason that Africans or deaf people need them, and must be “childlike, shy, submissive, and unintelligent.”

It also appears that paternalists find their charges difficult to manage. Here are some more traits common to the two lists: “aggressive,” unscrupulous (“weak conscience”), “disobedient, impulsive, suspicious” all these appear in both lists. Benefactors may find their charges difficult to manage because the benefactor’s goals differ from the beneficiary’s. For example, the Belgian benefactor wanted the Burundian to carry his possessions and his plunder. A 1922 Belgian decree authorized the colonizers to use forced labour in Burundi, which led to mass emigration of the African population. In another example, a few months ago hearing benefactors in charge of the Tennessee School for the Deaf demanded that all deaf pupils sign in English word order. Eighty-five students at the school resisted this decree; they were declared unmanageable and suspended.

The benefactor finds his charges difficult to manage not only because his goals differ from theirs, but also because he does not know their language, culture, and values — he has only self-serving stereotypes to misguide him. Borrowing a term from deaf authors Padden and Humphires, we might say that the benefactor, with his own goals and stereotypes, has a different “center” than the beneficiary. They can both look at the same thing and have very different perceptions, and this is especially true if they are both looking at the beneficiary, the African or the deaf person. A paternalistic authority is likely to give a very different description of his charges than the one they would give of themselves provided they have not internalized the stereotype promulgated by the authority. I call this the “parallax test” for identifying paternalism.

Applying this second test to our two groups, we find that most Africans would heatedly reject the descriptions of them given by the colonizers, and indeed most deaf people would reject those given by the hearing experts. Like the colonizers and the colonized, the hearing establishment serving deaf people and deaf people themselves have two different points of view, two different conceptions of deaf people, and two radically different agendas in America, as elsewhere in the world.

The main image is of the school at Gisuru. The image is from the school’s Facebook.